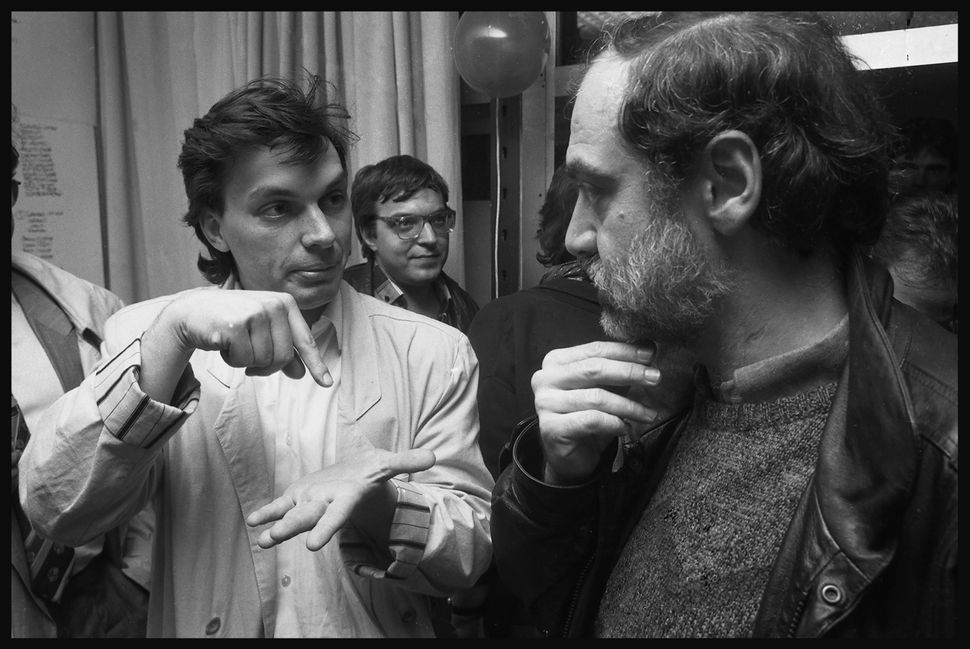

On the Avenue for the Victory of Socialism, Bucharest, December, 1985.

Hungary: the merriest barracks in the camp

In 1988, I was given permission to live in Hungary and moved to Budapest, one of the first western reporters allowed to do so. You could see what made this city so impressive – its great day in the sun was from 1867 until the First World War when Hungarians built Budapest to outshine Vienna. But during the Second World War, Budapest was bombed by the Allies then fought over by the invading Soviets. Four decades of Communist neglect followed, and by the 1980s many of the buildings in Pest looked like their facades were made of natural rock formations: pockmarked by bullet holes and covered in decades of grit and coal soot.

But even the Communists couldn’t ruin the countryside, especially in the hilly wine districts near Tokaj.

Plot 301 of the Central Cemetery, where leaders of the 1956 revolt were buried in unmarked graves. The police are watching me, Budapest. February, 1989.

Hungary: to rebury the past

No sooner had I moved to Hungary in 1988 than Janos Kadar, head of the Communist Party since 1956, was ousted by reformers. And even those reformers were pushed out in September 1989. Imre Nagy, Prime Minister in 1956 when Hungary tried to leave the Warsaw Pact, had been hung in 1958 and labelled a counter-revolutionary. But this was a lie that could no longer be told. Nagy and other leaders of the failed revolution were to be reburied.

The ceremony on 16 June 1989 attracted hundreds of thousands of Hungarians, but unlike the crowds I would photograph in Prague and Berlin and Warsaw, no one at Nagy’s funeral had come to celebrate. They had come to mourn their family members who had been shot, imprisoned, or had fled the country in the wake of 1956. It was as somber as a funeral, which, of course, it was.

The last Communist Party May Day, Budapest, 1988.